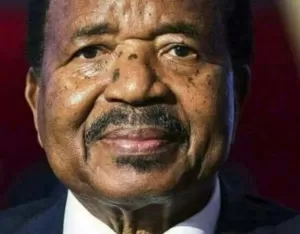

Glenda Jackson, fearless actor and politician, dies aged 87

Glenda Jackson, fearless actor and politician, dies aged 87

Her singular passion lit up performances from Women in Love to King Lear and drove her 23-year middle career as an MP

Glenda Jackson has died at the age of 87 after “a brief illness” at her home in London.

In a statement, her agent, Lionel Larner, said: “Glenda Jackson, two-time Academy Award-winning actress and politician, died peacefully at her home in Blackheath, London, this morning after a brief illness with her family at her side.”

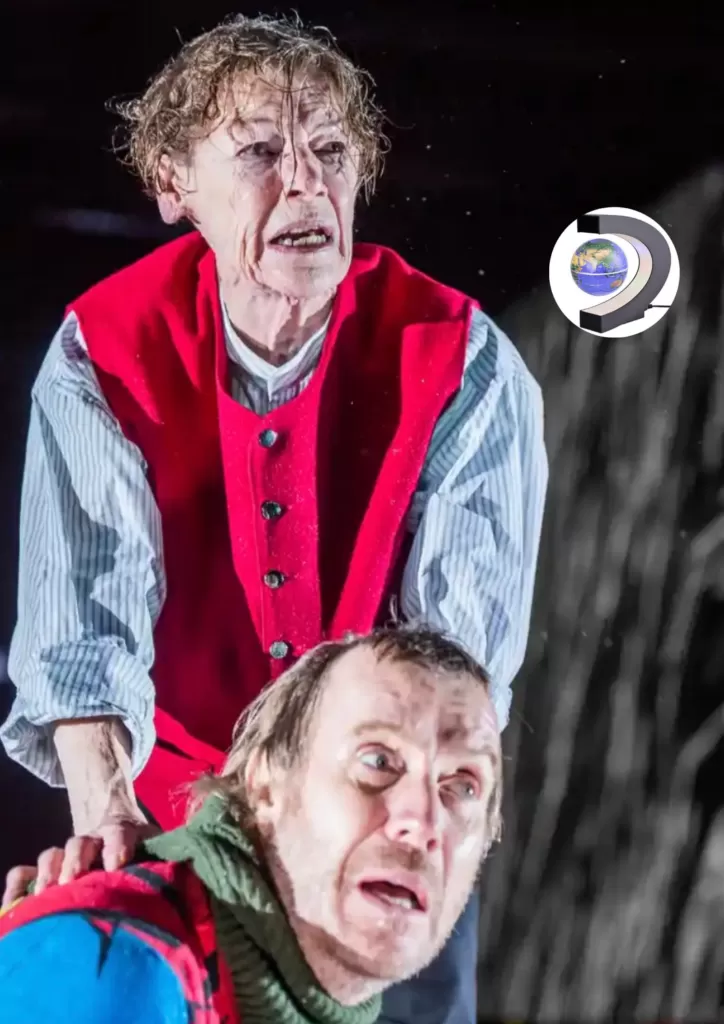

Jackson bestrode the narrow worlds of stage and screen like a colossus over six decades. Though such a Shakespearean tribute would undoubtedly have had the famously curmudgeonly actor reaching for her familiar catchphrase: “Oh, come on. Good God, no,” nothing less will do for a star who emerged from a 23-year career break to play king Lear at the age of 82.

Not only did she win an Evening Standard theatre award for that performance, but she brought the audience to its feet by playing up to her ferocious reputation with an attack on the awards’ sponsor. For decades, the newspaper had scorned her as an actor, opposed her as an MP, she said, “so I’m left thinking what did I do wrong?”

Jackson began life in Birkenhead, Merseyside, in 1936, the first of four daughters born to a bricklayer father and a mother who worked as a cleaner. Her early dreams of becoming a dancer were thwarted when she grew too tall, and she left West Kirby grammar school for girls at 15 for a job on the shop floor of Boots.

Discovering that she liked acting, after being persuaded by a friend to join the local Townswomen’s Guild drama group, she applied to the one drama school she had heard of, Rada, with the proviso that she could only afford to go if she won a scholarship. She duly did. She was still a student there when she made her professional stage debut in the seaside town of Worthing in 1957, in a two-parter by Terence Rattigan, Separate Tables.

Six years as a jobbing actor and stage manager in repertory theatres around the country eventually brought her to the attention of the RSC, which she joined in 1964 just as the director Peter Brook was making a mark with a season entitled Theatre of Cruelty. He cast her in Peter Weiss’s Marat/Sade, as a prisoner assigned to play Marat’s assassin, Charlotte Corday, a performance that was recalled years later by the playwright David Edgar as one of the best he had ever seen, in a production that “changed British theatre for ever”.

She went on to reprise the role on film in 1967, by which time she had already made a fleeting screen debut in Lindsay Anderson’s This Sporting Life. Her film career began in earnest two years later, when her performance as the abrasively sexual Gudrun, in Ken Russell’s adaptation of the DH Lawrence novel Women in Love, won her the first of two best actress Oscars, neither of which she turned up to receive. She later said she had bequeathed her statuettes to her mother, whose ferocious polishing soon rubbed the gilt away.

By the time she finished making Women in Love she was six months pregnant with her son, Dan, the only child of an 18-year marriage to fellow actor turned antique dealer Roy Hodges. But far from slowing down for a while, two years later she was back, in a rollercoaster of roles. Her achievements in 1971 included Tchaikovsky’s nymphomaniac wife in another Russell film, The Music Lovers; Queen Elizabeth I, in an influential TV six-parter Elizabeth R which won her two Emmys, and a mouthy, placard-wielding Cleopatra in the first of a series of comedy turns for the BBC’s Morecambe and Wise Show. In 1973 she won her second Oscar as sparring lover Vicki in the romantic comedy A Touch of Class.

Though she was outspoken about the lack of good parts for women, she continued to find them into her 50s, at which point she made the startling decision to give it all up and run for parliament. From her election in 1992 to her resignation in 2015, she turned her back on her previous stardom, devoting herself to representing the constituents of Hampstead and Kilburn in London as a Labour MP.

Any ambitions she may have had for a lead role in government were banjaxed by her outspoken opposition to the Iraq war. Grandstanding opportunities were limited to occasions such as the death of Margaret Thatcher, when she cut through sentimental parliamentary etiquette with her own salty verdict on an ideology of “greed, selfishness, no care for the weaker, sharp elbows, sharp knees”.

She followed her triumphal return to the theatre as King Lear with another award-winning performance, as the shuffling, vituperative 92-year-old widow A, in a Broadway revival of Edward Albee’s Three Tall Women, and as Maud, the Alzheimer’s-struck protagonist of Elizabeth Is Missing (of which Guardian TV critic Lucy Mangan wrote that she was “wonderful, in that vanishingly rare way that can come only from next-level talent as razor-sharp as it ever was plus 40 years of honing your technique, whetting both blades on 80 years of life experience.”)

She forsook her north London stronghold in her later years for a basement flat in the south London home of her son, Dan Hodges – now a political columnist whose views were markedly different from her own – where she gardened, watched her grandson growing up, and continued to pour the finest sort of scorn on any passing folly or hypocrisy.